Acquisition risk swap

September 24, 2024

Abstract

We introduce an acquisition risk swap (ARS), a type of subordinated risk swap that could be used

to hedge the risk of being unable to acquire a capability during an uncertain future time interval.

Examples of such scenarios include a nation being unable to procure specific military capabilities in

the event of a future conflict or a firm being unable to procure a product component in the event of

a future pivot to a new market. We describe the contractual structure of an ARS, pricing formulae,

and possible market structures that could facilitate the efficient exchange of ARS. Simulations of

ARS price distributions under a variety of example event probability and capability value models

indicate typical positive skew, implying the need for a writer of ARS to hedge their position. We

outline a market structure that decouples pricing and sale of ARS from creation of the capability

to be acquired. Participation in this market enables the writer of ARS to hedge its risk and is a

positive-sum outcome for both the writer of the ARS and the creator of the capability.

1 Introduction

Swaps are financial instrument that enable two or more parties to exchange value flows at pre-defined times

or upon the occurrence of precisely defined events. Subordinated risk swaps are a generic class of swaps that

trade a firm’s idiosyncratic risk (e.g., managerial or event risk) for a series of cash flows. We introduce an

acquisition risk swap, a type of subordinated risk swap designed to enable the acquiring agent (“acquirer”) to

hedge the risk of being unable to acquire a capability at an uncertain time in the future. In the case

of defense acquisition, which is the motivating driver of this work, an example of such a risk

is that associated with the widely reported shortage of 155mm shells used in modern artillery

pieces .

We argue that adoption of ARS by users of a capability might be desirable for at least three interrelated

reasons – risk reduction, efficiency, and transparency:

-

Risk reduction – the purchaser of the ARS will be able to plan for future contingencies with

increased certainty and will likely pay a lower cost for doing so if the event against which the

purchaser is hedging does come to pass.

-

Efficiency – ARS enable each party involved – the purchaser of the ARS, seller of the ARS, and

a downstream creator of the capability that may be desired in the future – to specialize, focusing

on their comparative advantages (of using the capability, determining the probability that the

capability is necessary, and creating the capability respectively) rather than the party that needs

to use the capability performing all three tasks likely suboptimally.

-

Transparency – as with any type of market, the publication (to a more or less limited audience)

of the prices resulting from exchange in that market are a signal of the extent to which the asset

traded in that market is demanded and can be supplied. In the case of an ARS, this translates to

transparency in the probability of (a) the time window over which a specified event might occur

and (b) the value that the acquirer places on the acquired capability. Analysis of the ways in

which the capability can be used in a particular context, in conjunction with the inferred value

the acquirer places on the capability, reveals aspects of the acquirer’s strategy in that context.

Depending on the context, this may or may not be a desirable feature of an ARS market. For

example, prices in an ARS market could be used to signal to a nation’s adversaries, or to a firm’s

competitors, an intent to take specific actions at a future time.

In Section 2 we outline the basic contract structure of an ARS and derive explicit formulae for pricing it under

multiple assumptions, some of which we then relax. Section 3 describes possible market structures that could

facilitate pricing and exchange of ARS, while Section 4 describes empirical distributions of ARS prices under

multiple different modeling assumptions. We close by describing possible generalizations of our work in

Section 5.

2 Asset definition and pricing

We outline the asset definition and pricing in discrete time; an extension to continuous time should be

straightforward. An agent that needs a capability during a future time interval {t,...,T} holds the ARS,

paying a coupon of mτ,τ ∈{0,...,t - 1}, where t ≤∞ (the ARS may never be exercised, in which case the

ARS is a perpetual obligation). When the capability is needed – the a priori unknown future time t –

the holder of the ARS ceases to pay the coupon and is delivered a capability that has value

vτ,τ ∈{t,...,T}.

We solve for the coupon rate mτ by finding such a value that makes the cash flows equivalent at time zero.

Defining the valuation V (t1,t2) = ∑

τ=t1t2-1βτ[mτδ(τ < t) + vτδ(τ ≥ t)], where β =  and r is the risk

free rate, the coupon payments are those values mτ that satisfy V (0,t) = V (t,T). With the simplifying

assumption that mτ = m, τ ∈{0,...,t - 1}, the coupon payment is m =

and r is the risk

free rate, the coupon payments are those values mτ that satisfy V (0,t) = V (t,T). With the simplifying

assumption that mτ = m, τ ∈{0,...,t - 1}, the coupon payment is m =  ∑

τ=tT-1βτvτ, or under the

additional assumption that the value of the acquired capability is equal at all times τ ∈{t,...,T - 1},

m = v

∑

τ=tT-1βτvτ, or under the

additional assumption that the value of the acquired capability is equal at all times τ ∈{t,...,T - 1},

m = v . Here, m is a random variable, as it depends on the random time interval {t,...,T - 1} over

which the capability is required. Modeling the time interval with the joint distribution (t,T) ~ p(t,T), we

take the coupon payment as the expected value of m,

. Here, m is a random variable, as it depends on the random time interval {t,...,T - 1} over

which the capability is required. Modeling the time interval with the joint distribution (t,T) ~ p(t,T), we

take the coupon payment as the expected value of m,  = E(t,T)~p(t,T)[v

= E(t,T)~p(t,T)[v ].

].

More generally, the interest rate rτ and the valuation of the capability vτ may vary in time. Interest rates

may be correlated with the existence or nature of the conditioning event; for example, conflict

could lead to shortages of basic necessities such as food and fuel, raising inflation which could

cause a central bank to raise interest rates [BK84]. The value of one capability immediately after

the inception of a conflict could be very high but decrease as time progresses, while another

capability could increase in importance as a conflict progresses. With these considerations in mind, a

more general valuation of the ARS is m = E(r,v,t,T)~p(r,v,t,T)[ ], where analogously

βτ =

], where analogously

βτ =  .

.

3 Market structure

We undertake a brief discussion of naive and more nuanced market structures for ARS, and discuss methods

by which price discovery for ARS is likely to occur. We leave in-depth analysis of possible market structures

for future work.

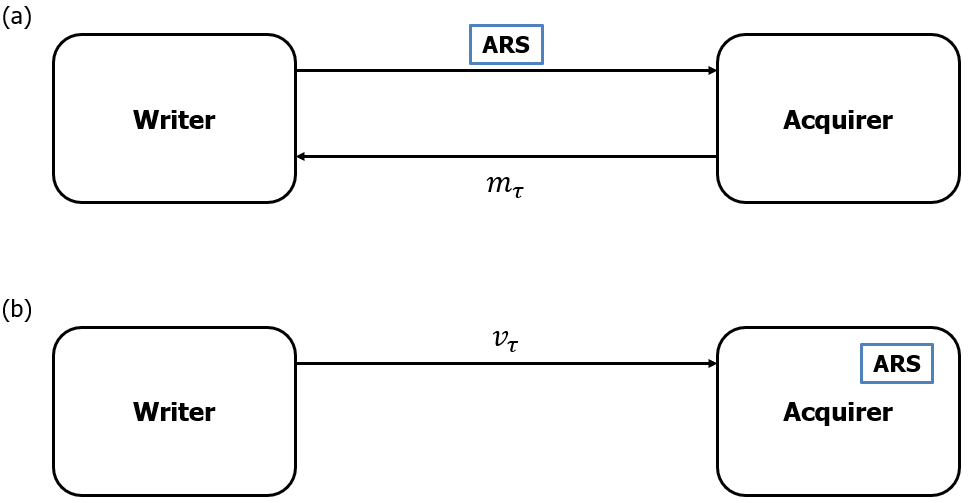

The mechanics of an ARS contract are specified in Section 2; a graphical depiction of these simple

mechanics is displayed in Fig. 1,

in which panel (a) refers to before the ARS is exercised by the holder and panel (b) describes the

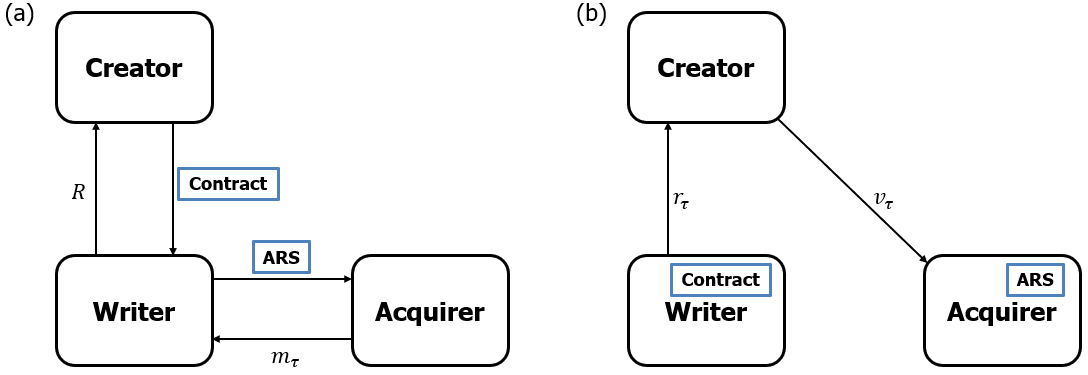

structure after it is exercised. We display a notional, more-developed market structure in Fig. 2.

In this example, the writer sells the ARS to the acquirer and hedges the risk it takes on in doing so by

contracting with a creator of the capability (e.g., in the 155mm shell example, a manufacturer capable

of rapidly retooling to create shell casings), paying that creator a fixed-fee retainer R at the

initial time period. If the triggering event occurs, the writer pays a further stream of cashflows rτ

(which are possibly zero) to the creator; the creator creates the capability and delivers it to the

acquirer.

A more complex market structure, such as the one outlined in the previous paragraph and displayed in

Fig. 2, has at least two benefits over the naive market structure displayed in Fig. 1:

-

Decoupling of financial valuation from physical delivery. In general, there is no reason to believe

that a firm with the expertise valuing an ARS – i.e., a firm that believes it can accurately and

precisely estimate the probability distribution of the window over which a capability would be

needed – would also have the expertise required to rapidly create that capability. For example, a

geopolitical risk firm that believes it can assess the likelihood and duration of a conflict between

two nations is probably not the same firm that can rapidly manufacture a large quantity of shell

casings.

-

Incentive to participate in the market due to speculation and innovation. The writer of an ARS

might believe that the conditioning event will occur in the very distant future, or has a very low

probability of occurrence at all, and therefore believe that the negotiated stream of income mτ

represents a low-risk profit opportunity. The creator of the capability, on the other hand, may

have no opinion about the likelihood of the event at all, but assesses it can very rapidly create

the required capability with almost no advance warning and at a cost exactly equal to rτ in

perpetuity; in this case, the retaining fee R is essentially a risk-free profit for the creator.

How might the price of an ARS be discovered? As with other swaps, this would likely depend on the

liquidity of the underlying capability that the acquirer is hedging and the relative market power of the

acquirer(s) compared with the writer(s). In the monopsonistic case, and when the capability is relatively

liquid or even standardized, it would seem likely that the acquirer would run an English reverse auction (or

similar commonly practiced single reverse auction). When the capability is less liquid the contracted price

could be negotiated over-the-counter between the writer(s) and acquirer. We explore other mechanisms for

price discovery in Section 5.

4 Simulation

We outline some empirical statistical properties of the ARS under simple statistical models and an example market

structure.

4.1 Statistics of price distributions

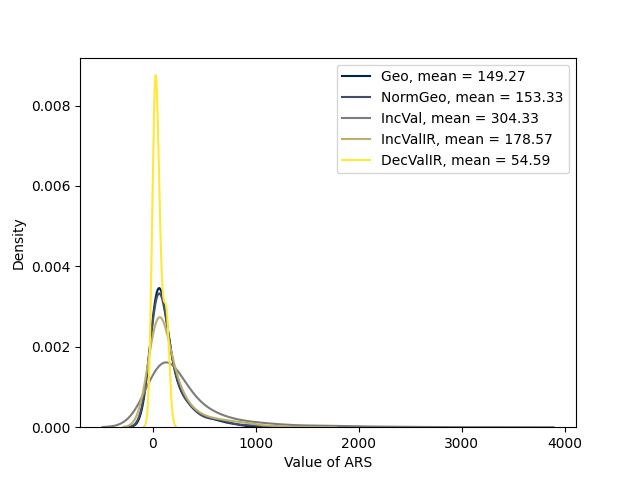

We briefly compare empirical distributions of ARS price under different generative models of event time

interval {t,...,T - 1}, value v, and interest rate r. We emphasize that these distributions are rough indicators

of behavior only as the price of ARS will depend crucially on estimation of value and event time interval

probability that will very likely be highly context-dependent. Specializations to specific operational contexts

are not in scope for this work.

Each pricing example uses the naive event probability distribution p(t,T) = p(t)p(δt) = Geometric(t|ρt) Geometric(δt|ρδt),

where T = t + δt. Each example begins with a notional risk-free rate of 4%, capability value of v = 100

(abstract numeraire), and ρt = ρδt =  . Empirical density functions of price are displayed in Figure 3.

. Empirical density functions of price are displayed in Figure 3.

We describe scenarios in terms of changes to the default parameters listed above.

-

(Geo) – no changes to the specifications listed above.

-

(NormGeo) –  ~ Normal(v,σv2). By Jensen’s inequality, the linearity of the identity function,

and the conditional independence of v and (t,T), the price distribution in this scenario is

theoretically identical to that of Geo.

~ Normal(v,σv2). By Jensen’s inequality, the linearity of the identity function,

and the conditional independence of v and (t,T), the price distribution in this scenario is

theoretically identical to that of Geo.

-

(IncVal) – vτ = vτ-1(1 + ϵ), where ϵ ~ Exponential(ϵ|1), modeling an on-average-precipitous

increase in the value of the capability for the duration of the event.

-

(IncValIR) – simultaneously (a) the value of the capability deterministically increases from v to

asymptotically approach a new steady state according to vτ = v∕2 + v∕[1 + exp(-(τ - t))] and

(b) the interest rate moves from stochastic fluctuation about the steady state r- = 4% to the

higher steady state r+ = 6.5%. Stochastic fluctuation is modeled via a single factor short rate

model, rτ = rτ-1 + θ(r*- rτ-1) + ξ, where ξ ~ Normal(0,σξ2) and r* is the equilibrium rate

and θ > 0.

-

(DecValIR) – simultaneously (a) the value of the capability deterministically decreases according

to vτ = v∕exp(-(τ - t)) and (b) the interest rate fluctuates according to the same model

presented in IncValIR.

In these examples, ARS price distributions generally have excess mass in their right tails, meaning that there is

substantial tail risk that the actual value of the cash flows to the right of the event start date have higher

value than what would be suggested by the expected value pricing formulae presented earlier. We will discuss

hedging strategies in Section 5.

4.2 Market structure

We construct a simulation of a simple form of the market structure presented in Fig. 2. There is a single

acquirer who has a mean reservation price  ~ Normal(m,σ2), where

~ Normal(m,σ2), where  is computed under the distribution

p(t,T) = Geometric(t|ρt*) Geometric(δt|ρδt*), where T = t + δt and the estimates ρt* and ρδt* are publicly

known. The acquirer’s observed price of the ARS is given by m ~ Normal(

is computed under the distribution

p(t,T) = Geometric(t|ρt*) Geometric(δt|ρδt*), where T = t + δt and the estimates ρt* and ρδt* are publicly

known. The acquirer’s observed price of the ARS is given by m ~ Normal( ,σ

,σ 2). There are n = 1,...,N

writers of ARS who compete to sell a single ARS to the acquirer via an English reverse auction.

They have heterogeneous beliefs about the start and stop probability of the event, modeling it as

ρt(n) ~ Normal(ρt*,σρt*2) and ρδt(n) ~ Normal(ρδt*,σρδt*2) conditioned to lie in (0,1). There are ℓ = 1,...L

manufacturers who can create the capability desired by the acquirer. Each manufacturer has a private reserve

value Rℓ ~ Normal(m,σR) they require to accept a contract for manufacture at an unknown future date, and

each has a marginal production cost of cℓ ~ Normal(m∕2,σc). Before time τ = 0, the acquirer

conducts an English reverse auction to purchase the ARS from a writer. Then, the successful writer

conducts an English reverse auction on reserve price with the manufacturers. If this market clears,

meaning that the the writer who wins the auction has a price for the ARS is less than or equal to

the acquirer’s maximum willingness to pay and, similarly, that the manufacturer who wins the

auction has a reserve price for manufacturing that is less than or equal to the writer’s maximum

willingness to pay, the model advances in discrete time, with contract mechanics as specified in Section

2.

2). There are n = 1,...,N

writers of ARS who compete to sell a single ARS to the acquirer via an English reverse auction.

They have heterogeneous beliefs about the start and stop probability of the event, modeling it as

ρt(n) ~ Normal(ρt*,σρt*2) and ρδt(n) ~ Normal(ρδt*,σρδt*2) conditioned to lie in (0,1). There are ℓ = 1,...L

manufacturers who can create the capability desired by the acquirer. Each manufacturer has a private reserve

value Rℓ ~ Normal(m,σR) they require to accept a contract for manufacture at an unknown future date, and

each has a marginal production cost of cℓ ~ Normal(m∕2,σc). Before time τ = 0, the acquirer

conducts an English reverse auction to purchase the ARS from a writer. Then, the successful writer

conducts an English reverse auction on reserve price with the manufacturers. If this market clears,

meaning that the the writer who wins the auction has a price for the ARS is less than or equal to

the acquirer’s maximum willingness to pay and, similarly, that the manufacturer who wins the

auction has a reserve price for manufacturing that is less than or equal to the writer’s maximum

willingness to pay, the model advances in discrete time, with contract mechanics as specified in Section

2.

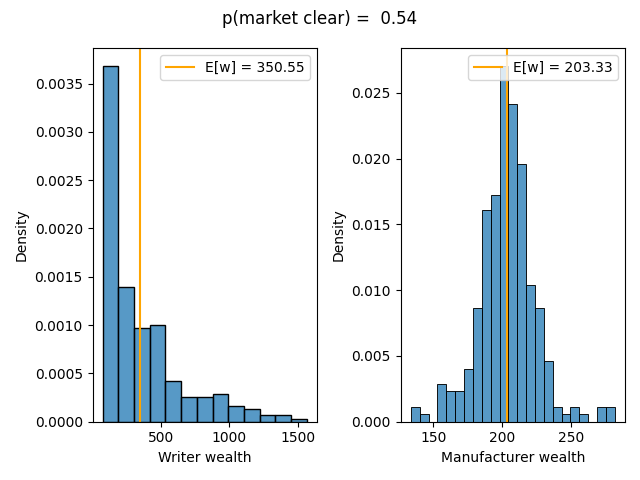

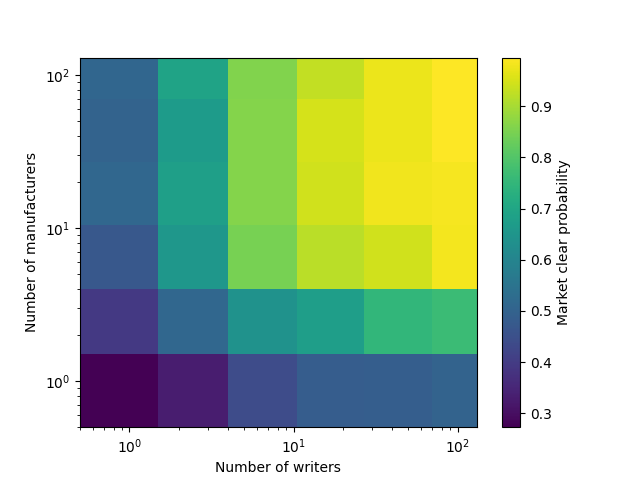

We display wealth distributions of successfully matched writers and manufacturers in Figure 4 and market

clearing probability as a function of number of writers and manufacturers in Figure 5. Monte Carlo

simulations of this market structure suggest that the market clears with high probability even with

relatively low participation. For example, even with only two writers and two manufacturers

participating in the marketplace, the market clears more than half of the time. (Under this model, a

market with only one potential writer and 10 manufacturers clears almost half of the time – 44% –

while an ARS market with a healthy five writers and 20 manufacturers clears a full 92% of the

time!)

5 Generalizations and structural considerations

We constructed a pricing and market structure framework for acquisition risk swaps (ARS), a type of

subordinated risk swap that eliminate the risk that an agent faces from needing to acquire a costly capability

during an unknown future time interval. However, we made multiple simplifying assumptions that, in our

judgement, would be eliminated in a commercial implementation of an ARS marketplace. We outline

several unaddressed shortcomings of the present work each of which could be ground for further

research.

-

Event probability distribution – probably the most glaring assumption we made for each of

our simulations was that of events starting and stopping according to independent Bernoulli

trials. The pricing formulae described earlier do not depend on such an assumption. In reality,

the probability of events for which an ARS would be appropriate to hedge, such as conflict

or large-scale business transformation, would have rich structure conditioned on complex

representations of world state (e.g., geopolitical factors or the competitive structure of a firm’s

target marketplace). Event times might also exhibit nontrivial correlation structure (e.g., if a

conflict starts sooner than expected it could also end sooner than expected). Such dependence

could be modeled using an appropriate copula structure.

-

Valuation of the capability – we have assumed that the acquirer can place a monetary value on

the capability it seeks to acquire and that the writer can assess what that monetary value is. In

practice each of these statements may not be true. A lower bound to the value of an additional unit

of a capability could be the sum of the marginal costs of each of its components (including labor

and properly amortized operational expenditures) but this bound may be very weak. Estimating

the acquirer’s value function would probably be a nontrivial task for both the writer and the

acquirer, but could be facilitated by advances in reinforcement learning [SHGS15]. The acquirer

may face the risk that it systematically understates its true valuation of the capability (e.g., by

valuing it at only the sum of its marginal costs of production plus a constant value that does not

incorporate the discounted benefits of future use) and consequently faces lower market supply

than expected.

-

Interest rate dynamics – interest rates may co-vary substantially with the probability of the

conditioning event. For example, interest rates and the capability to be acquired may both be

affected by geopolitical dynamics.

-

Market structure – we have outlined one market structure, in addition to the naive one defined

by the mechanics of the ARS contract, that could create additional market efficiencies in terms

of hedging risk and decoupling firms’ comparative advantages. However, there are likely other

market structures, depending on operational context, that could incentivize participation by

different firm types (e.g., different production capacities, risk preferences, or investing time

horizons). In some applications, markets could need to place constraints on writers and creators

(e.g., based on capitalization or security requirements).

-

Price discovery – the nature of the acquired capability would likely dictate the method by which

its price is discovered. Non-exquisite, low-marginal cost capabilities (e.g., commodity drone parts)

could be created by many parties, leading to very liquid markets; other capabilities (e.g., bespoke

defense manufacturing) might exhibit complexity such that the market for capability creators,

at time of the ARS’s inception, is much less liquid. The price signal created by the ARS could

facilitate capital investment in that market if the timescale on which the ARS writers’ market

expects the capability to be needed, Et~p(t)[t], is compatible with the requried investing timeline

(e.g., timeline required to build a manfacturing facility).

Acknowledgements

The views stated in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of the

U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. Distribution Statement A: approved for public release,

distribution is unlimited.

References

[BK84] Daniel K Benjamin and Levis A Kochin. War, Prices, and Interest Rates: A Martial

Solution to Gibson’s Paradox. 1984.

[SHGS15] Tom Schaul, Daniel Horgan, Karol Gregor, and David Silver. Universal value function

approximators. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1312–1320. PMLR,

2015.

and r is the risk

free rate, the coupon payments are those values mτ that satisfy V (0,t) = V (t,T). With the simplifying

assumption that mτ = m, τ ∈{0,...,t - 1}, the coupon payment is m =

and r is the risk

free rate, the coupon payments are those values mτ that satisfy V (0,t) = V (t,T). With the simplifying

assumption that mτ = m, τ ∈{0,...,t - 1}, the coupon payment is m =  ∑

τ=tT-1βτvτ, or under the

additional assumption that the value of the acquired capability is equal at all times τ ∈{t,...,T - 1},

m = v

∑

τ=tT-1βτvτ, or under the

additional assumption that the value of the acquired capability is equal at all times τ ∈{t,...,T - 1},

m = v . Here, m is a random variable, as it depends on the random time interval {t,...,T - 1} over

which the capability is required. Modeling the time interval with the joint distribution (t,T) ~ p(t,T), we

take the coupon payment as the expected value of m,

. Here, m is a random variable, as it depends on the random time interval {t,...,T - 1} over

which the capability is required. Modeling the time interval with the joint distribution (t,T) ~ p(t,T), we

take the coupon payment as the expected value of m,  = E(t,T)~p(t,T)[v

= E(t,T)~p(t,T)[v ].

].

], where analogously

], where analogously

.

.

. Empirical density functions of price are displayed in Figure

. Empirical density functions of price are displayed in Figure

is computed under the distribution

is computed under the distribution